4 Week 4

5 Policy: The City of Cape Town Municipal Spatial Development Framework

5.1 Summary

The City of Cape Town Municipal Spatial Development Framework (MSDF) is a policy document that guides spatial planning and land use decisions for the City of Cape Town. It’s a requirement of the Spatial Planning and Land Use Management Act (SPLUMA) that all municipalities have an MSDF (Republic of South Africa 2013). SPLUMA is pretty interesting legislation. It was introduced in 2013 to rationalise South Africa’s fragmented planning law. One of the most exciting (in theory) things about it is the development principles it introduces. According to law in South Africa, all planning decisions taken by government must take into account the principles of:

Spatial Justice;

Spatial Sustainability;

Efficiency;

Spatial Resilience; and

Good Administration

Pretty cool, right? Except it’s very difficult to define all of these things, and so it’s very common for developers to argue that a car-centric gated development located in the middle of nowhere will contribute to spatial justice and sustainability.

That’s why it’s extremely important in South Africa to have clear planning policy that’s informed by evidence (including remote sensing data). I think Cape Town does a pretty decent job in this regard – their policy is generally sound, and informed by strong analysis. Where things can break down is at the interface between policy and individual land use decisions, which get made with little reference to policy or spatial planning principles. So I think there’s a lot of work to be done in reconciling policy with the actual decisions that get taken.

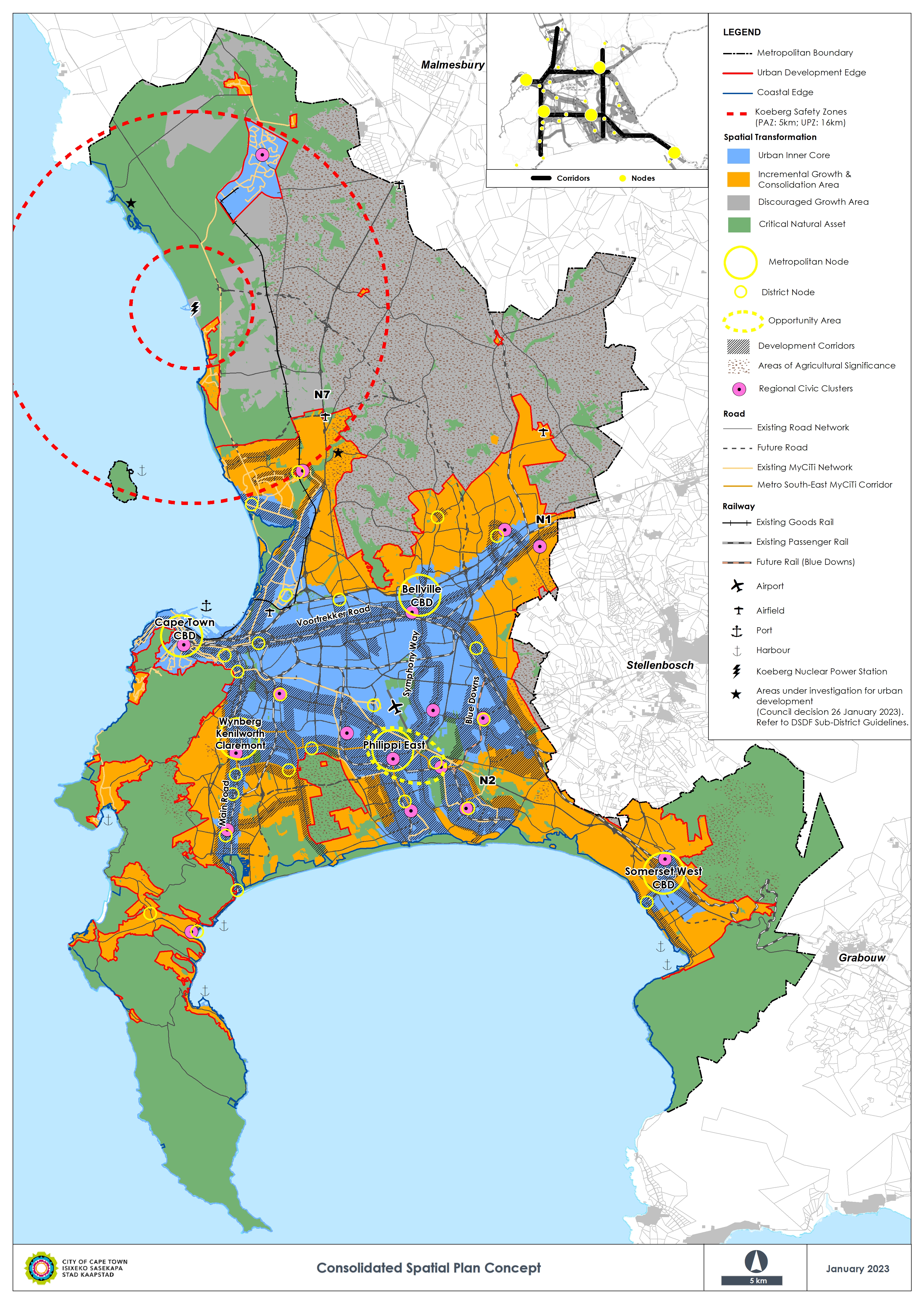

The Cape Town MSDF is summed up in this image, which has been nicknamed the ‘blue turtle’ by planners in South Africa – the blue areas (which resemble a turtle) are the areas of the city where development is encouraged:

One of the key issues highlighted in the MSDF is the need to stop outward urban expansion (or sprawl), and to keep developing within the ‘blue turtle’. This has been difficult to do for many reasons, including the increase of gated private developments on the urban periphery. One of the other reasons is a phenomenon that’s been on the rise since COVID-19: informal land invasion. This is a complex issue that is driven by deep poverty, inequality, and housing shortages, and those root causes need to be addressed. However, the consequences of informal expansion are serious, as sites meant for facilities like housing, schools or clinics are no longer available. Last year, Driftsands Nature Reserve had to be decommissioned as it had been occupied illegally, and the ecosystem was degraded beyond rehabilitation.

The MSDF highlights this issue as follows:

The urban development edge has made provision for development opportunities at strategically located expansion areas located close to areas of intense urbanisation pressures, mass land invasion, significant levels of persistent informality and increasing levels of unauthorised occupation of land nullifying scheduled government housing projects (City of Cape Town 2022).

And this video talks about the MSDF’s approach to housing, which is where I believe remote sensing data has significant application for the city:

5.2 Applications

The city uses remote sensing data quite a lot already, and Cape Town has high-resolution LIDAR data that has been used to map informal settlements in the city by Shoko and Smit (2022). I think that, given the issues with housing supply highlighted above, and the increasing issue with informal land invasions happening in the city, the city could explore using remote sensing data to identify areas that may be vulnerable to future invasion.

This is an idea that was proposed by Tellman, Eakin, and Turner (2022) in Mexico City. The authors of that study wanted to link remotely sensed imagery to urban policy in order to identify areas that may be vulnerable to future informal expansion. However, their method was not possible without high-resolution time-series data. It would be interesting for the City of Cape Town to explore developing a similar model using Worldview imagery, which is high-resolution imagery that has to be purchased. A fairly straightforward approach would be to train a classification model on sites that have recently been invaded, along with the areas adjacent to them, and use the model to identify similar areas. These sites could then be evaluated qualitatively to determine whether they should be given additional protection.

Issues around informality are complex, and there is a lot of nuance that I’ve left out above. The city’s first obligation has to be addressing the root causes that are driving increasing levels of informality. But it’s also true that, as more sites are invaded, the city’s ability to do that is compromised, as it has less land to work with to deliver the infrastructure that’s needed to address the bigger problem. I think that a classification algorithm trained on high-resolution imagery could be a simple intervention that helps to identify which areas are in need of additional protection.

5.3 Reflections

I mentioned earlier that the MSDF is a requirement of national legislation. In South Africa, municipalities are required by law to have something called an Integrated Development Plan (IDP), which sets out the budgeting priorities for the municipality. The IDP is renewed every five years. An MSDF – which is a separate document – is part of the IDP, and gives spatial expression to the policies described there. It’s meant as a long-term plan, and operates according to a 10-or-20-year vision. This is where things get a bit weird, because the MSDF is part of the IDP, but the IDP operates on a shorter timeline than the MSDF.

I used to work in provincial government, and we’d offer support to the 24 municipalities in the Western Cape. In March/April every year there was always a big headache trying to make sure that all municipalities re-approved their IDPs and MSDFs, in order to ensure that they were legislatively compliant and protected from litigation in the event of disputes over land-use decisions (Western Cape municipalities are home to some particularly litigious residents).

Anyway, this is a long-winded way of saying that a big part of the job of a spatial planner is ensuring that the policies and interventions they propose are compliant with legislation or other policy, and that this can mean that much of the work of policymakers is actually spent on this rather than the content. That’s also why remote sensing data has a lot of potential: it can really enhance and speed up the process of obtaining information about how a city is developing, which is critical to developing sound policy.